Ett spännande verk har precis färdigställts i centrala Göteborg: ”A Line” är placerad ovanför och nedanför trappartiet utanför Scandinaviums entré.

Verket har utförts av den tyska konstnären Judith Hopf i ett samarbete med Florian Zeyfang och består av en orange linje som ser ut att vara ritad i ett enda svep. Markmålningen utgår från Scandinaviums ursprungliga kulör och mönstret som bildas kan till exempel föreställa en ishockeyspelare eller publik som jublar, vilket är fritt för egen tolkning. Konstverket, som beskrivs som komplext och lekfullt, knyter därmed an till ishockey- och musikevenemangen som äger rum i Scandinavium.

Curatorerna Åsa Norberg och Jennie Sundén samtalade med konstnären när hon var på besök i Göteborg för att se det färdigställda verket.

You have recently installed your public commission ”A Line” outside the event arena Scandinavium here in Göteborg. The work consists of an unbroken line in orange that winds over a fairly large surface area. The line is painted in the kind of paint that is used for street markers. Can you tell us a little bit about your ideas behind the work?

– As you know, there is this area in front of Scandinavium where people meet and are standing in line. People might be excited to go for a game, a music or sportive event. It is a special social situation in such a moment, when you have to be in a group. It is chaotic and at the same time very organized. The events inside Scandinavium may have a somewhat similar format as the outside social gathering, by following the rules of the ice hockey game on the one hand, but never knowing where the puck will go on the other hand. I thought it would be nice to do something with that movement. Just like playing, music and sports in general have these chaotic movements and you as a visitor are also in a move outside. I thought it could be interesting to make a documentation or a drawing of how it could look like, when an unexpected movement will cause a goal or something like that. Like a scribble, and quite chaotic. I thought that it would be nice to do something spontaneous looking.

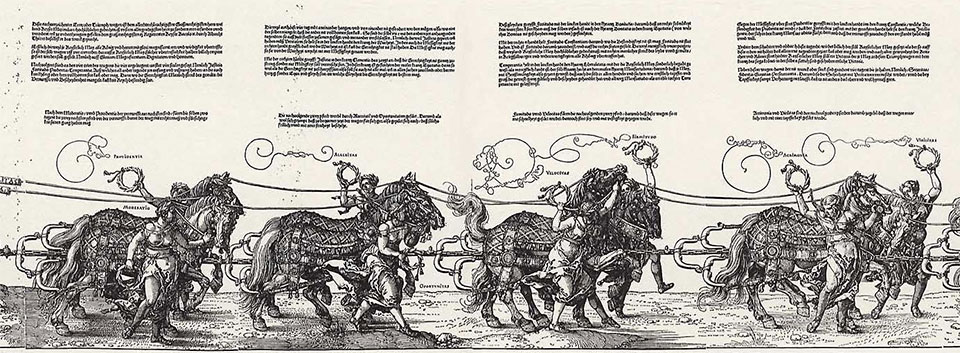

Florian Zeyfang, an artist college who collaborated with me within this project, brought in that Albrecht Dürer was already thinking of this kind of lines and circles, that are part of the famous wood print called Triumphzug Kaiser Maximilians.

On top of the figures in the print, there are these wild curly lines in the air. And we thought that maybe this is a way of showing that there is movement, like a documentation of something, not naturalistic but something more physical maybe. And in addition to this connotation there was also the book by Lawrence Stern called Tristram Shandy. In this novel theses lines appear, even though its 350 years old, in the written text. So, the line is also close to writing in a way.

I was also very much inspired, and maybe that is the most obvious, by the artist Saul Steinberg who was an American artist who did a lot of comics or one-line drawings in the New York Times. He was working with the chaotic versus the non-chaotic, sense making – not sense making line-storytelling. It was figurative more or less. And I always laugh about his drawings because he is changing the perspectives and sometimes you see it as from above and then it flips as if it would be frontal again. Let’s say, he is ignoring the central perspective.

Yes, the line is of course something that we all have some kind of relation to, both physically, spatially, mentally and as an idea. The line is also a very strong symbol for borders in different ways. And as an artist the line is almost like the starting point for an artwork and for the sportsperson more of an endpoint or a goal in a way. As you told us you have had these and many other thoughts in mind. But are there also other meanings or readings to the line that have been important to you, in general, for you personally or connected to your art practice?

– The line is always a bit like writing. But I always understood writing with words more like a chain. Of course, there are the connotations to graffiti or street art in this artwork. If you enlarge writing you are quite close to the very original idea of the graffiti I guess. I have looked at ancient graffiti, not the pop cultural orientated, but engravings in museums that are saying ”Hi, I was here”. And I always think that it is quite charming that people try to communicate with lines or with this non-sense sense-making. In my practice, I don’t often have the chance to do things like this. Mostly I do sculptures, but in some of them I have had the chance to work with the line. As with the “Exhausted vases” and the series of “Flock of Sheep,” which were both orientated towards a very naive understanding of what you could do with a line. I think that the most fascinating thing is, that you have two points on a drawing and it’s a face. I think it is also showing how much humans are putting themselves in center and always trying to mirror back themselves even if it’s only two points and a smiling line. The more you try to make it simple, the more people try to mirror in it. I think it is fascinating and that is what I have found out in other sculptures, too. In the space in front of Scandinavium, I isolated that line and this time it is not on top of a sculpture, but using the surroundings. That way it gives the viewers a chance to be part of the sculpture, rather than mirror their own gaze in it.

Your specific line looks like it has been scribbled down or like a quick illustration on an iPad. Outside Scandinavium the line is extremely enlarged to a totally different scale. What do you feel has happened in this translation and what is your experience being on site?

– It is a bit like a dream, that you would do something spontaneous, or allow yourself to make some scribbles on a piece of paper, and then imagine that it could be placed in the street in a really large scale. That is an intense and nice imagination, because normally you would not think it would make sense to enlarge these little notice points. I like it a lot, because it says that the small ideas or starting points might be looked at in bigger contexts. And that it is not only representative but also a bit challenging, since it is not perfect. It is more in process and not developed in the sense of a drawing as a very organized mindset or something. It keeps this spontaneity and I think it fits the sports theme as well.

“A Line” is one of few public works that you have made. In what way is the process of working with public art different from working in the context of doing exhibitions in institutions?

– First of all, I think it’s interesting because you work within so many different fields. It is not so often that you have the chance to work with architects and I think that is very constructive. I also had the chance to work together with Florian Zeyfang as an artist colleague to bring in other ideas. I think I like the process, which is more open and it also has a more firm-like structure. You can take on responsibilities like other firms, and it is not so much a symbolic action, but more of a process that grounds you quite good somehow.

I am also astonished that the end result looks the same as it was planned. It is so amazing. But of course, all architects are laughing about that. But for me it is a bit shocking. If I do exhibitions in the context of a gallery or museum, everything is much more specific. For example, I am changing the positions of the works in relation to the atmosphere, the lights and where people will go through the museum space. And that is not possible in this kind of project; of course, you have to plan all that beforehand. And I think It is fun to deal with all these challenges, is the work big enough, is it too small, can you see it and so on. I really like it and I didn’t know that I like that. So, I am grateful for the opportunity.

What is your relation to public art in general and what do you think public art can do/offer?

– I don’t know whether I have a specific relation to art in public space. I think it is always interesting to fight for public spaces. And presenting art in public space shows, that there is also something that has not only to do with consuming things, but that there are places to meet or places to hang out or places to be pointed at, because there is this specific historical moment appearing. I think it would be cool if artists were counted in as much as possible, when it comes to how the public is confronted with that. It is a great opportunity to get places of both conflict and fun. And it is not too often in our present times, that such an opportunity is given, because we always have so much to consume. You know, it is more about having coffee or ice-cream and that’s of course also nice. Here in Göteborg you still seem to have a lot of public spaces, but I think they might be vanishing due to a consumer orientated culture of selling. Public art is a chance to hold some spaces and then of course it has also educative moments. It is showing that you allow a society with moments of different usage, understanding, discussion and I like that. I would not agree with a tradition, where public sculpture was mainly understood as something where you have to do monuments. I think it would be nice to support more conceptual understandings of ways how we could live together.

Do you have any favorite public art work?

– I have many! I love Louise Bourgeois’ spider “Maman” in front of the stock market in London. And then I love a lot the late sculptures of Jean Dubuffet in Chicago and New York. They are these “circle crackle” or disorganized drawings, but made like three-dimensional shapes in a strange plastic material. I think they are really cool. And Max Ernst in Paris in front of the Centre Pompidou. And Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely, I think they are the best. Tinguely did all these water fountain machines and if you go there in winter time, then they are frozen into ice, and it is really beautiful. They represent not only their function but also bringing in the weather somehow. I was quite astonished to see them in winter. There is also this tradition of very sad sculptures in Germany, especially in the North, where you always feel depressed looking at these figurative things. When you walk down the street, you always feel like, – Oh a flower, oh a dog, oh a sculpture, and I always feel like, – Oh my god it is so sad the way the people are looking at you. Nowadays I can laugh about it, but when I was younger I thought it was so annoying. But I like a lot of things. I even like the works of Jeff Koons. They are so super shiny.

Your relation towards public sculpture is also changing in time. When I was younger I would not even recognize public sculpture and now I see them. They are so present, it is really nice.

Judith Hopf

föddes 1969 i Karlsruhe, Tyskland, och bor och arbetar i Berlin. Hon är professor och vice rektor för konst vid den inflytelserika Städelschule Art Academy i Frankfurt. Tillsammans med andra inflytelsefulla konstnärer som arbetade tillsammans i Berlin på 1990-talet, ordnade Judith en serie salonger på b_books, en välkänd bokhandel i stadsdelen Kreuzberg. Judith har ställt ut på Hammer Museum/Los Angeles, Museion/Bolzano, Neue Galerie/Kassel, Maumaus/Lissabon, PRAXES Center for Contemporary Art/Berlin, Malmö Konsthall, Studio Voltaire/London och Badischer Kunstverein/Karlsruhe. Hon har också deltagit i Documenta XIII, La Biennale de Montréal och Liverpool Biennial.

Konstverket ”A Line” är en del av Scandinaviums ombyggnadsprojekt som slutfördes förra året och har tagits fram i samarbete med Higab, Got Event, 02landskap arkitektkontor, ABAKO arkitektkontor och Göteborg Konst.